Proud to be an Indigenous Educator

Growing up in Santa Maria, Manuela Cruz (Liberal Studies, '21) dreamed of attending Cal Poly. Though her path was littered with obstacles, her quiet determination kept her moving forward until one life-changing day in an elementary school classroom pointed her firmly in the right direction.

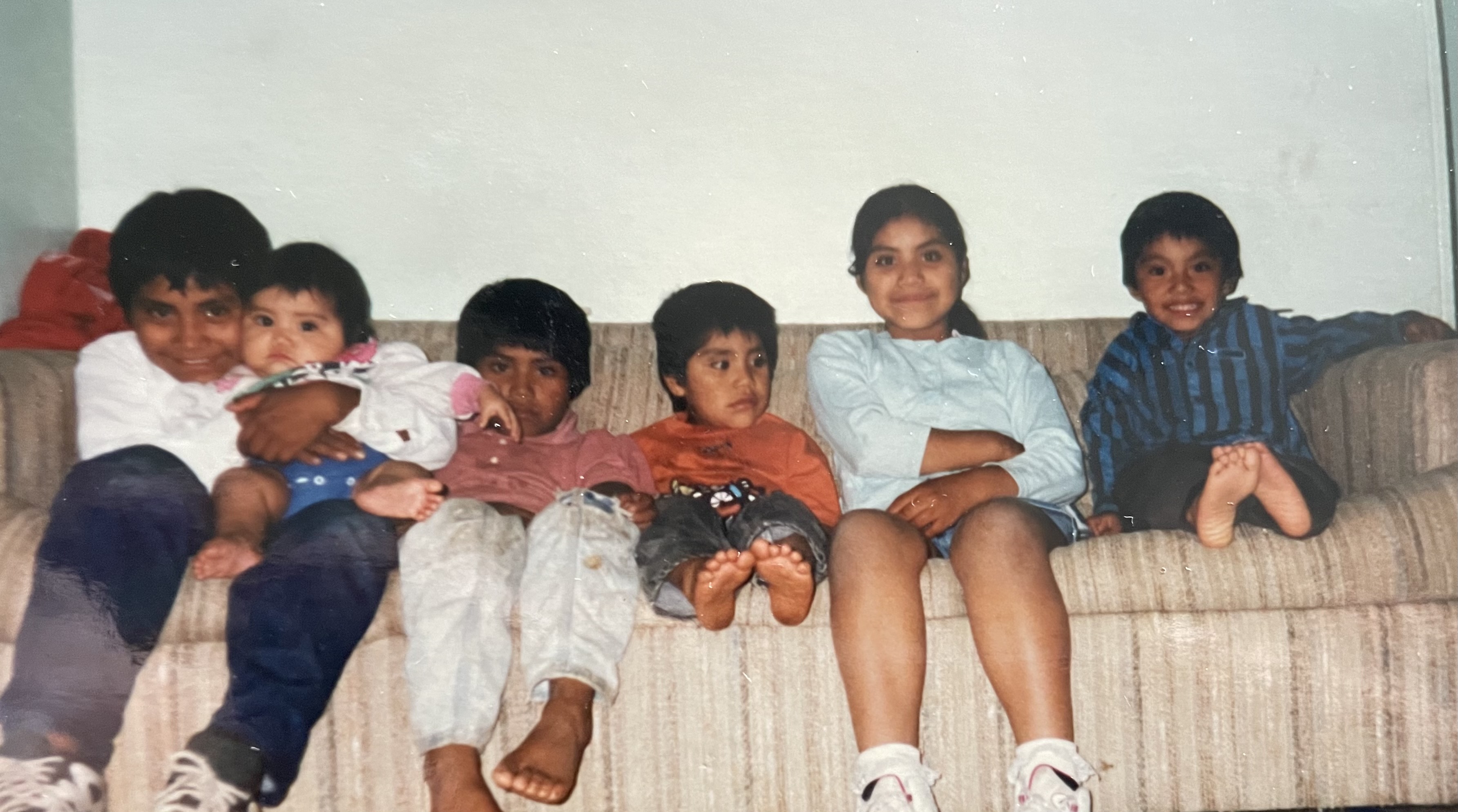

Cruz, who spent her first eight years near Oaxaca, Mexico, remembers her early childhood fondly: "I was happy playing with my cousins and my friends. We would leave the house, be out all day and come back when it was dark. I was really free. When I look back and think about my parents, though, it was not as good.”

After Cruz survived what doctors predicted would be a deadly bout of meningitis, her parents decided to move the family to the U.S. to better care for their children. From a carefree life, Cruz landed in a place where she didn’t know anyone and had to stay inside all day because both parents worked.

During her own schooling, Cruz never could have predicted that one day she’d find great joy in walking into a classroom.

During her own schooling, Cruz never could have predicted that one day she’d find great joy in walking into a classroom.

“School was the hardest part” about life in the U.S., she said. “I started falling behind. Everything was two to three times harder because I didn't know the language. I didn't have friends till fourth or fifth grade. I felt invisible.”

With that background, discovering she had a passion for teaching was a complete surprise.

THE CHILDREN WERE DELIGHTED. THEY HAD WHAT CRUZ HAD NEVER HAD—A TEACHER WHO LOOKED AND SPOKE LIKE THEM.

When the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy (DACA) was put in place, Cruz enrolled in a nursing program at Allan Hancock College. Waiting in place in 2012, she took an education course that included classroom observation.

While sitting with a group of students, Cruz tried to connect with the shyest one, asking him a direct question. One of the other students informed her that the boy didn’t speak English or Spanish, only Mixteco, an indigenous language.

“That’s OK,” she said, “I speak Mixteco.”

The children were delighted. They had what Cruz had never had — a teacher who looked and spoke like them.

“I loved how they were so happy and they were so proud of telling other students that they spoke Mixteco,” Cruz said. “It was a completely different experience than what I had, and I thought, if I can give them a different view of their home language, something I’ve never had, I’d love to do that. Growing up I never thought I could be anybody. I never thought I could have a good job or a career. I never saw anyone that had a good job that was indigenous like I was, that spoke Mixteco like I did. Representation is so important. This is what I needed, this is what students need, and I felt like I could be this, I could do this.”

Though her passion for teaching never wavered, Cruz struggled to form an identity as a teacher while an undergraduate at Cal Poly, a predominantly white university. Once again, her classmates and role models didn’t look like her and didn’t share or understand her background or experiences.

She found a sense of belonging and community at the campus Dream Center, a space dedicated to providing services and support to undocumented students.

“I started going into the Dream Center and started seeing more students of color and seeing this isn’t just my experience,” Cruz said. “I felt like that was my community, this was my place.

“The staff advocates were Kat Savallos, the coordinator, and Catherine Trujillo. I felt like no matter what, they would be there and help support students. It was my first experience of being in a community that was always there for each other. It was the only place that would understand truly what I was going through.”

GOING TO CAL POLY, I FOUND WHO I AM, WHERE I AM, WHERE I BELONG. I’M AN INDIGENOUS WOMAN. THAT’S WHO I AM. I BELONG HERE.

—MANUELA CRUZ

During her senior year, Cruz helped to co-found and served as vice president of the Educators of Color Club. The club has a dual mission. Club members come together to support one another so future education students don’t experience the same identity struggles Cruz and other club founders did.

They also see building up the community as part of their role as educators. Many of them are the children of farmworkers and intimately understand the challenges and difficulties families in that industry face. The club's outreach projects have supported the children of farmworkers through a holiday toy and book drive and the donation of backpacks full of school supplies.

Club co-advisor and education Professor Tina Cheuk finds Cruz’s dedication inspiring.

“What most impressed me about Manuela’s educational journey is that in spite of all of these personal adversities, she found inner strength and a commitment to persist and continue her education both to better the life of her multigenerational family and to work for students who share her similar lived experiences and identities in the Santa Maria community,” Cheuk said.

Despite her struggles, Cruz is proud to be a Cal Poly graduate.

“Going to Cal Poly, I fou

Cruz is pursuing her multiple subject teaching credential and master’s degree in curriculum and instruction through Cal Poly’s School of Education. When she completes her program, she plans to teach fifth or sixth grade in Santa Maria.

“I would love to see more indigenous students go into education, to change that view that I don’t belong in any of the spaces,” Cruz said. “The indigenous community in Santa Maria has so much potential, but as a community we’re not doing enough to support them. So I hope from Cal Poly that we do more and we come together to help our community because if we don’t help them no one’s going to.” //

Read more about Inclusive and Equitable Communities in Welcome to the Water, Under the Sea, and Equal Access to the Cosmos